Nuclear Fusion: too late for the climate

Fusion energy is highly unlikely to be ready in time to help meet climate targets. Here's why.

Preface

The post below was originally published on theconversation.com, under the title “Conservatives’ ‘nuclear fusion by 2040’ pledge is wishful thinking”. It came about after my twitter rant was picked up. Apparently 15,000 people have read the piece, which is pretty cool.

Really the point is not just about the UK Conservative Party’s policies, but about the trap of techno-optimism as a valid approach to decarbonisation in general.

Fusion is merely a clear example of this general problem, where the complexity of the science (and often sloppiness of science communication) allows non-experts to harbour unjustified levels of optimism about development timescales.

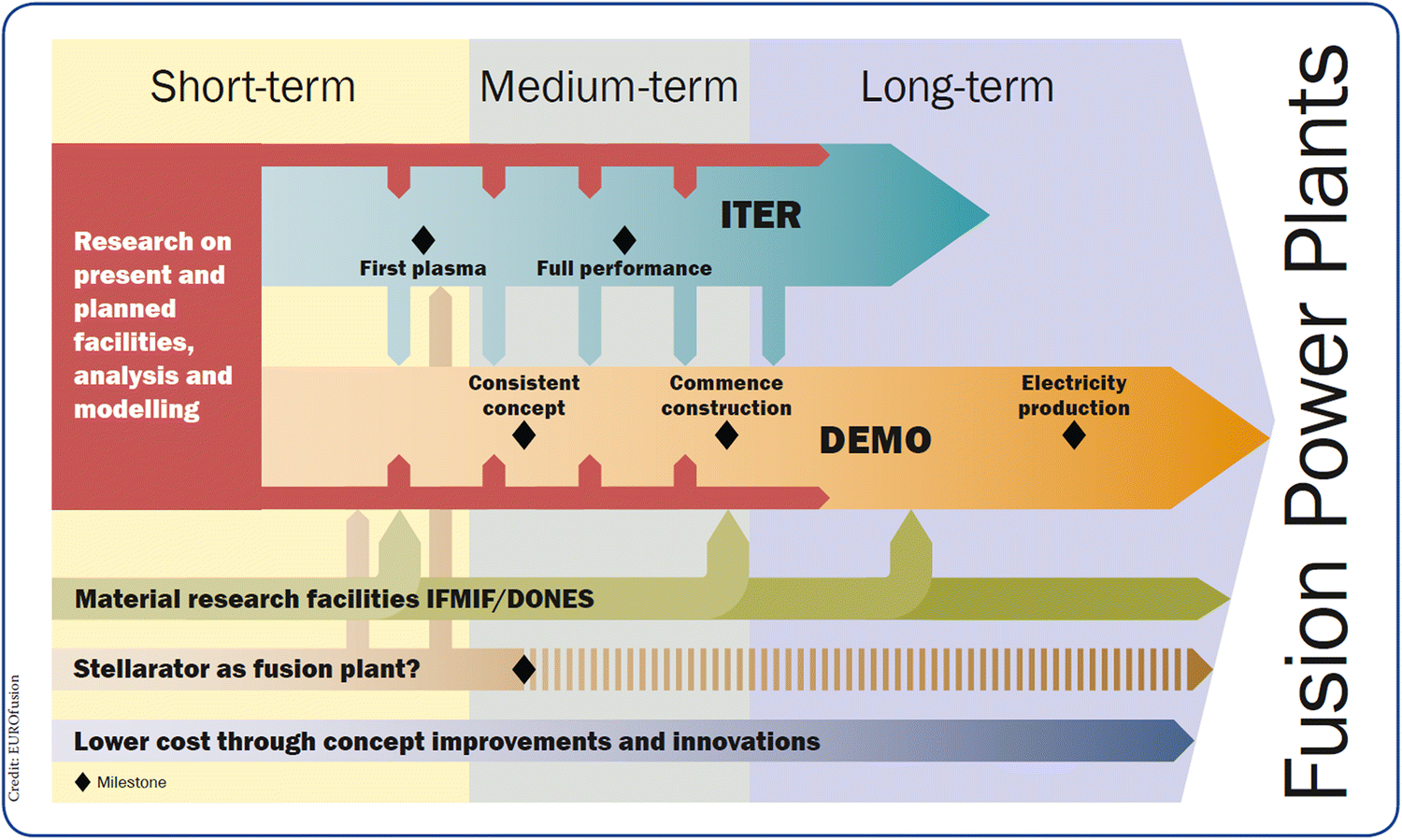

The Gantt chart above from the EuroFusion Roadmap (the EU fusion research consortium, and main global effort) lays out the problem. Notice the conspicuous absence of projected dates…

Conservatives’ ‘nuclear fusion by 2040’ pledge is wishful thinking

The UK’s governing Conservative Party has announced a new package of climate policies, including £220m for research into nuclear fusion reactors to provide clean energy “by 2040”. Although additional funding is welcome news to fusion researchers like me, it isn’t an effective response to climate change.

It’s easy to see why such a pledge is appealing though. Nuclear fusion is the process that powers stars like our sun. Unlike current nuclear power plants – which split atoms in a process called fission – nuclear fusion binds atomic nuclei together. This releases much more energy than fission and produces no high-level nuclear waste.

A fusion reactor would also produce zero carbon emissions and wouldn’t run the risk of a nuclear meltdown. Fusion could produce energy regardless of wind conditions or daylight hours, and wouldn’t require enriched uranium, which can be repurposed for nuclear weapons.

As good as this all sounds, nuclear fusion is unlikely to play a major role in fighting climate change. To understand why, we need only look at the current state of fusion research.

Fusion: for the stars, for now

For decades, the performance of fusion devices has been improving – the capacity of scientists to confine hot hydrogen plasma has improved by a factor of 10,000. This plasma has to be over 100,000,000°C in order for the hydrogen nuclei to fuse and generate energy.

The next big step is ITER, a huge project involving 35 nations, under construction in the south of France. ITER’s purpose is to test our ability to confine plasma for long enough and at a high enough density and temperature. Its goal is to be the first fusion device to produce more energy from the plasma than is put into it.

But ITER isn’t a power station, it’s an experiment. The plan is to build a demonstration fusion power plant – called “DEMO” – after ITER shows it’s possible for the plasma to generate a net gain in energy. But ITER isn’t likely to reach this goal until 2035.

The EU fusion roadmap assumes DEMO comes some time afterwards, likely around 2050 or later. The Tory promise of 2040 is extremely optimistic. A DEMO power plant needs to solve several problems which ITER won’t address. ITER’s power is produced in the form of neutrons which hit the reactor’s internal walls, but DEMO needs to actually turn that power into electricity.

One of the biggest challenges is that a fusion reactor has to generate some of its own fuel. Two types of hydrogen are needed – deuterium, which is abundant in seawater, and tritium, which is rare on Earth because it decays into helium with a half-life of only 12 years. DEMO will need to combine the neutrons from the plasma with lithium to produce new tritium fuel, in a process called “tritium breeding”.

Unfortunately, prototypes of this crucial technology can’t even be tested until ITER starts producing copious high-energy neutrons, in 2035. The UK has a solid research plan working towards solving all of these problems, but there isn’t much that can be done to accelerate this timeline.

Failing leadership on climate change

In 2018, the IPCC released their 1.5°C report, which explained that the world must reach net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050 in order to limit future warming to 1.5°C. It’s unlikely that commercial fusion power plants will exist in time for that, and even once a first-of-its-kind DEMO power plant is operational, hundreds would still need to be built to seriously dent global emissions. None of this sits well with the 2040 date the Conservatives have promised.

Even if a new green energy technology like fusion is realised before 2050, that’s far too late for the 1.5°C target anyway. “Net-zero by 2050” assumes that emissions have been constantly decreasing from now until 2050. As it’s the total amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere that sets the level of eventual global warming, it’s cumulative emissions that matter.

Even if we could snap our fingers on December 31, 2049 and replace all fossil fuel plants, the world would have already emitted twice as much carbon as the budget allows. Sound climate policy involves cutting emissions as soon as possible, and any further delay makes the task even harder.

As with any research, nuclear fusion might not work. Despite the best efforts of researchers, it’s still possible that there’s an unforeseen roadblock. But the climate won’t wait for us if we trip up.

Any convincing climate policy requires huge investments across many sectors, from domestic heating to road transport to agriculture. Even a complete decarbonisation of the electricity grid is only one part of the solution. The Committee on Climate Change’s net-zero report laid this all out starkly for policymakers – only mentioning nuclear fusion once in 227 pages. The idea of a single panacea is simplistic fantasy.

So why fund fusion? The likely role for fusion would be as an energy source in a post-carbon society. It’s well worth funding it for that reason alone, and it’s possible that an unexpected breakthrough will ensure it can reduce emissions after all. In fact, research into all sorts of new technologies could help make reducing emissions easier, such as industrial carbon capture and storage.

The allure of fusion makes it a good distraction from the failures of the current government’s science and climate policy. The Committee on Climate Change has set 25 targets that need to be met to ensure the UK is a net-zero society by 2050. The government is currently only on track to meet one of them.

This funding is also of little consolation to laboratories who are worried about the impact of Brexit on UK science, and their international staff who rely on freedom of movement. In fact, the government has yet to commit to paying to participate in the EU DEMO programme in the case of a no-deal Brexit.

Climate policy should prioritise deploying proven technologies immediately, without relying on speculative solutions. Stopping climate change is too important to leave to the last minute.